A case study in PDF forensics: The Epstein PDFs

ArticleDecember 22, 2025

ArticleDecember 22, 2025

About Peter Wyatt, PDF Association

The recent release of a tranche of files by the US Department of Justice (DoJ) under the “Epstein Files Transparency Act (H.R.4405)” has once again prompted many people to closely examine redacted and sanitized PDF documents. Our previous articles on the Manafort papers and the Mueller report, as well as a study by Adhatarao, S. and Lauradoux, C. (2021) “Exploitation and Sanitization of Hidden Data in PDF Files: Do Security Agencies Sanitize Their PDF files?,” in Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Workshop on Information Hiding and Multimedia Security, illustrate the importance of robust sanitization and redaction workflows when handling sensitive documents prior to release.

This article examines a small random selection of the Epstein PDF files from a purely digital forensic perspective, focusing on the PDF syntax and idioms they contain, any malformations or unusual constructs, and other technical aspects.

PDFs are more challenging to analyze than many other formats because they are binary files that require specialized knowledge, expertise, and software. Please note that we did not analyze the contents of the PDF documents. Not every PDF was examined. Any mention of products (or appearance in screen-shots) does not imply any endorsement or support of any information, products, or providers whatsoever. We are not lawyers; this article does not constitute legal advice

We offer this information, in part, as some of the Epstein PDFs released by DoJ are beginning to appear on malware analysis sites (such as Hybrid-Analysis) with various kinds of incorrect analysis and misinformation.

26 December 2025 update

After we'd completed our analysis the DoJ released a new dataset, DataSet 8.zip. This new ZIP file is 9.95 GB compressed and contains over 11,000 files, including 10,593 new PDFs totaling 1.8 GB and 29,343 pages (the longest document has 1,060 pages). DataSet 8 also contains many large MP4 movies, Excel spreadsheets, and various other files. The first PDF in the set of 10,593 PDFs is VOL00008\IMAGES\0001\EFTA00009676.pdf, and the last file is VOL00008\IMAGES\0011\EFTA00039023.pdf. A cursory analysis shows pdfinfo properties similar to those from the earlier datasets, but we have not otherwise analyzed this new dataset.

Since our original post, various social media and news platforms have also been announcing “recoverable redactions” from the “Epstein Files”. We stand by our analysis; DoJ has correctly redacted the EFTA PDFs in Datasets 01-07, and they do not contain recoverable text as alleged. As our article states, we did not analyze any other DoJ or Epstein-related documents.

For example, the featured image in this Guardian news article (which was also picked up by the New York Times) corresponds to VOL00004\IMAGES\0001EFTA00005855.pdf, as can be easily determined by searching for the Bates Numbers in the EFTA “.OPT” data files. The information in this EFTA PDF is fully and correctly redacted; there is no hidden information. The only extractable text is some garbled text from the poor-quality OCR and, as expected, the Bates Numbers on each page.

In the few reports we investigated (including from Forbes and Ed Krassenstein on both X (formerly Twitter) and Instagram), these stories misrepresent other DoJ files that were not part of the major DataSets 01-07 release on December 19 under the EFTA. All PDFs released under EFTA have a Bates Number on every page starting "EFTA". These include “Case 1:22-cv-10904-JSR Document 1-1, Exhibit 1 to Government’s Complaint against JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A.” (see page 41) and “Case No: ST-20-CV-14 Government Exhibit 1” (see page 19). These PDFs, previously released by the DoJ, do contain incorrect and ineffective redactions, with black boxes that simply obscure text, making “copy & paste” easy to recover the text that's otherwise hidden. Clearly, DoJ processes and systems in the past have inadequately redacted information!

The files we examined

The tranche released by DoJ on Friday, December 19 is available as seven “data sets”, most easily downloaded as seven ZIP archives totaling just under 2.97 GB. Each ZIP file contains a similar folder structure, with DataSet 6 being the odd one out with an extra top-level folder. Once unzipped, the total size is 2.99 GB. The tranche contains 4,085 PDF files, a single AVI (movie) file (located in the folder VOL00002\NATIVES\0001), and 2 data files (.DAT and .OPT) for each ZIP archive. The “.OPT” files appear to be CSV (Comma-Separated Values) but lack a heading row, while the “.DAT” files contain information about the Bates numbering. The analysis we provide here is limited to the PDF files.

The PDF files are named and ordered sequentially within the folder structure, starting with “EFTA00000001.pdf” in VOL00001 and ending with “EFTA00009664.pdf” in VOL00007, indicating that at least 5,879 PDF files remain unreleased.

A random sampling of the PDFs for visual review suggests that they are a mix of single and multi-page full-page photos and scanned content. OCR (Optical Character Recognition) was used to provide some searchable and extractable text in at least some files. “Black box” style redactions (without text reasons) are apparent. When done correctly, this is the appropriate way to redact, far more robust than pixelating text. The PDFs we sampled did not include any obviously “born digital” documents. Various news sites are reporting very heavily redacted documents within this tranche.

File validity

A precursor to most forensic examinations is to establish whether the PDF files are technically valid (that is, conform to the rules of the PDF format), since analyzing malformed files can easily lead to incorrect results or wrong conclusions. Combining tools that use different methods provides the broadest possible information while ensuring that tooling limitations are fully understood. However, if the basic file structure or cross-reference information is incorrect, various software might then draw different conclusions and/or construct different Document Object Models (DOMs).

In addition to basic file structure, incremental updates (if any), and cross-reference information, PDF validity assessments include the objects that comprise the PDF’sDOM as well as the file structure, incremental updates, and cross-reference information. To assess relationships between objects in the PDF DOM, some forensic analysis tools leverage our Arlington PDF Data Model, while others use their own internal methods.

Our analysis of file validity, using a multitude of PDF forensic tools, identified only one minor defect (invalidity); 109 PDFs had a positive FontDescriptor Descent value rather than a negative one. This is a relatively common (but minor) error, typically associated with font substitution and font matching, that does not affect the validity of the files overall. One specific forensic tool reported a PDF version issue with some files, related to the document catalog Version entry, which prevented the tool from further verifying those specific PDFs.

PDF versions

I’ve previously written about the unreliability of PDF version numbers. Still, for forensic purposes, they may provide insight into the DoJ’s software, and whether improved software could have performed better.

I used two different but commonly used PDF command-line pdfinfo utilities on different platforms (Windows and Ubuntu Linux) to summarize information about these PDF files. When run against the full tranche of PDFs, I got two very different sets of answers! Immediately, my spidey senses started to tingle, and I was once again reminded of a key lesson in digital document forensics – you should never trust a single tool!

| Reported PDF Version | Count Tool A | Count Tool B |

| 1.3 | 209 | 3,817 |

| 1.4 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.5 | 3,875 | 267 |

| TOTAL (should be 4,085) | 4,085 | 4,085 |

The PDF version in the file header, “%PDF-x.y”, is nominally the first line in every PDF file (based on the not-unreasonable assumption that the PDF files have no “junk bytes” before this PDF file identifier). Using the Linux command line, you can run in Linux “head -n 1 file.pdf” to extract the first header line from each PDF and compare it with the reported results from each tool. Or run in Linux “grep -P --text --byte-offset "%PDF-\d\.\d" *.pdf” to confirm that there are no junk bytes prior to the PDF header line.

The reason for the difference reported in the table above is that Tool B is not accounting for the Version entry in the document catalog of PDFs with incremental updates. We’ll next investigate whether this is due to malformed files or a programming error. When properly accounting for incremental updates, however, Tool A is correct.

Using the same pdfinfo output (and again comparing results from both tools), we can also quickly establish the following facts:

- No PDF is tagged

- No PDF is encrypted

- No PDF is “optimized” (technically, Linearized PDF)

- No PDF has any annotations

- No PDF has any outlines (bookmarks)

- No PDF contains any embedded files

- None of the PDFs are forms

- None of the PDFs contains JavaScript

Page counts range from 1 (in 3,818 PDFs) to 119 pages (in two PDFs), totaling 9,659 pages across all 4,085 PDFs.

Incremental updates

PDF’s incremental updates feature allows multiple revisions of a document to be stored in a PDF file. As the name implies, each set of deltas is appended to the original document, forming a chain of edits. When read by conforming PDF software, a PDF is always processed from the end of the file, effectively applying the deltas to the original document and to any previous incremental updates. Both the original document and each incremental update can be recognized by their respective “xref” and “%%EOF” markers (assuming that the PDF files are structured correctly).

For this investigation, we started by examining the very first PDF in the tranche: VOL00001\IMAGES\0001\EFTA00000001.pdf. This PDF had different PDF versions reported by different versions of pdfinfo. A simple trick to check if a PDF contains incremental updates is to search for these special markers while treating the PDF as a text file (which it isn’t!):

$ grep -P --text -–byte-offset "(xref)|(%%EOF)" EFTA00000001.pdf

371340:xref

371758:startxref

371775:%%EOF

372977:startxref

372994:%%EOF

373961:startxref

373978:%%EOF

These results (sorted by byte offset) indicate that EFTA00000001.pdf contains two incremental updates after the original file. The lack of an “xref” marker before the last two “startxref” markers indicate that neither incremental updates uses conventional cross-reference data, but may use cross-reference streams (if any objects are changed).

Bates numbering

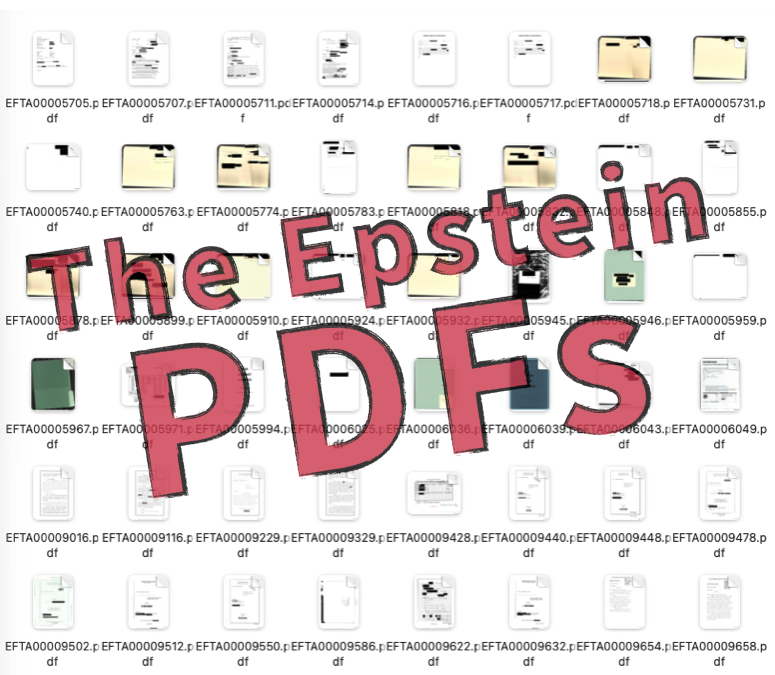

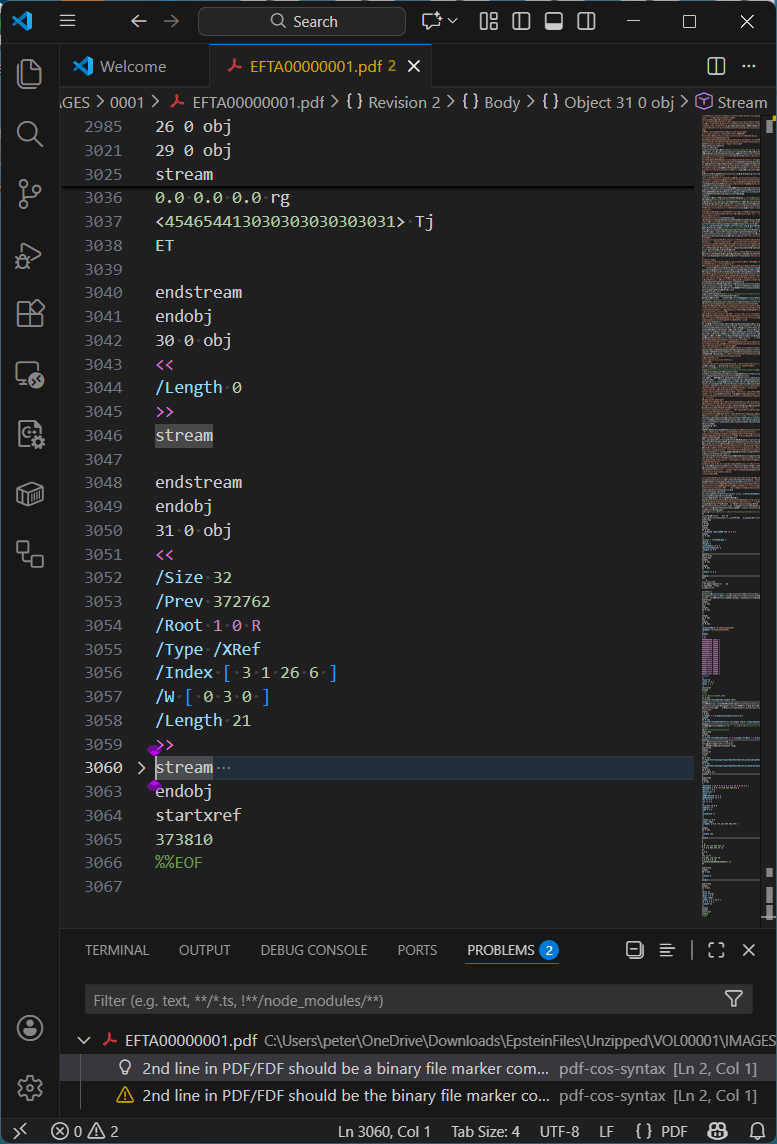

As referenced above, Bates numbering is the process by which every page is assigned a unique identifier. For this tranche of Epstein PDF files, Bates numbers were added to each page via a separate incremental update, as shown below in Visual Studio Code with my pdf-cos-syntax extension. Note that DoJ’s PDFs are primarily text-based internally, making forensic analysis a lot easier - and the files a lot bigger.

Observations:

- Line 2984 is the end-of-file marker for the file version, and line 2985 starts a new incremental update section.

- Lines 2985-2987 define object 26, the unembedded Helvetica font resource used by the Bates number.

- Lines 2997-3020 are the modified page object (object 3), replacing the page object in previous revisions of the file.

- Line 2999 is the page Contents array, comprising five separate content streams, with the 3rd stream (object 29) being the Bates numbering added in this incremental update. Object 30 is an empty content stream that could have been removed by an optimization process.

- Line 3034 sets the Helvetica font to 12 point.

- Line 3037 uses a hexadecimal string to paint the Bates number onto the page.

The idiom for this final incremental update, which adds the Bates number to every page, appears in all the PDF files we selected at random for investigation. This specific incremental update always uses a cross-reference stream (/Type /XRef) and relies on the previous incremental update, in which the document catalog Version entry is set to PDF 1.5.

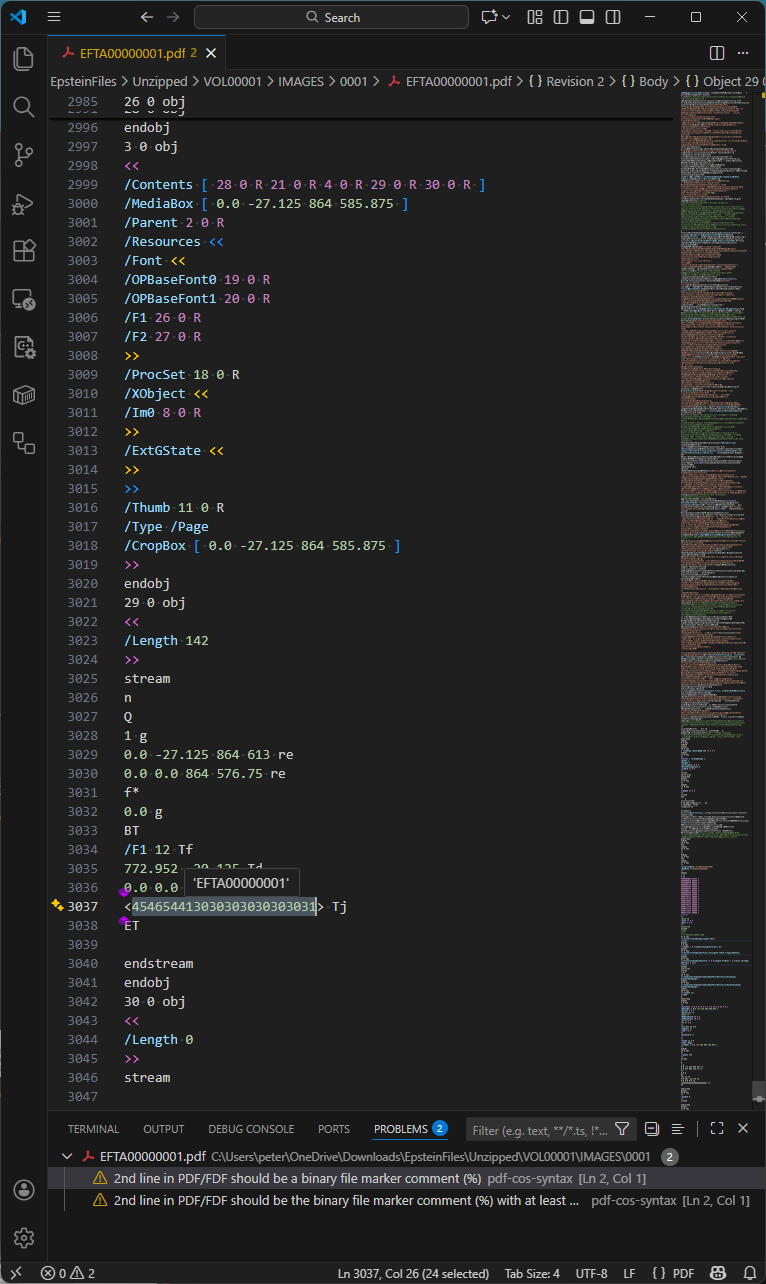

The first incremental update

The VSCode pdf-cos-syntax extension also indicates (correctly!) that the original PDF is missing the required (when the PDF contains binary data, which most do) comment as the second line of the file that indicates to software that the PDF file needs to be treated as binary data (ISO 32000-2:2020, §7.5.2). Although the missing comment does not make the PDF invalid per se, without such a marker close to the top of each PDF, software may think the PDF is a text file, and thus potentially corrupt the PDF by changing line endings, which would break the byte offsets in the cross-reference data. In this PDF, the first incremental update adds this marker comment after a lot of binary data, which is pointless.

As mentioned above, the first incremental update changed the document catalog Version entry to PDF 1.5, as we see in this next screenshot:

Observations:

- Lines 2953-2984 are the incremental update section.

- Line 2954 is a PDF comment. PDF comments always start with a PERCENT SIGN (

%) and may occur in many places in PDF files. Effective sanitization and redaction workflows typically remove all comments from PDFs because they may inadvertently disclose information, but this exact comment appears in 3,608 other PDF files. The origin or meaning of this comment was not further investigated. - Line 2964 upgrades the PDF version to 1.5. At first glance, this may appear to be perfectly valid PDF, but it is technically incorrect because the file header is

%PDF-1.3yet the Version key was only added in PDF 1.4 - this is what the strict file validation tool mentioned above had noticed. As object 24 is a compressed object stream (lines 2966-2973) and object 25 is a compressed cross-reference stream (lines 2974-2981), the indicated version should be PDF 1.5. As a practical matter, however, this level of technical detail does not impact operation or behavior of PDFs. - Line 2984 is the end-of-section “

%%EOF” marker for this incremental update section.

As this section of the PDF uses compressed object streams, specialized PDF forensic tools must be used… simple search methodologies, such as those mentioned above, may not identify everything!

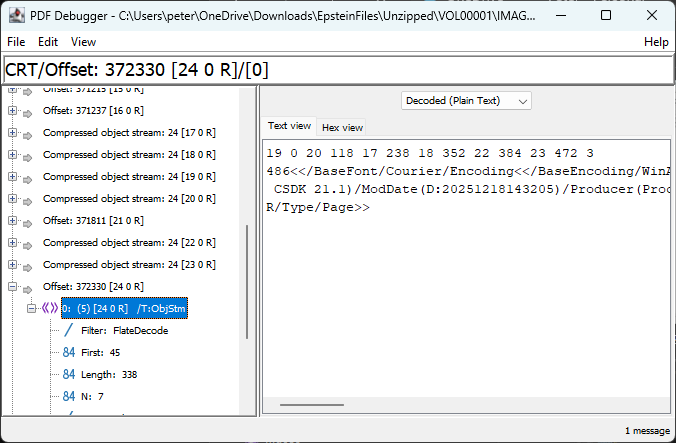

We know that there are 7 objects (because we find /N 7) inside the object stream:

As per PDF’s specification, ISO 32000-2:2020, §7.5.7, the first line of integers is interpreted as N pairs, where the first integer is the object number and the second integer is the byte offset relative to the first object in the object stream.

| N | 1st integer (object number) | 2nd integer (start offset) | Explanation | Content |

| 1 | 19 | 0 | Type1 Font object for OPBaseFont0 (Courier) | <</BaseFont/Courier/Encoding<</BaseEncoding/WinAnsiEncoding/Type/Encoding>>/Name/OPBaseFont0/Subtype/Type1/Type/Font>> |

| 2 | 20 | 118 | Type1 Font object for OPBaseFont1 (Helvetica) | <</BaseFont/Helvetica/Encoding<</BaseEncoding/WinAnsiEncoding/Type/Encoding>>/Name/OPBaseFont1/Subtype/Type1/Type/Font>> |

| 3 | 17 | 238 | Document information (Info) dictionary | <</CreationDate(D:20251218143205)/Creator(OmniPage CSDK 21.1)/ModDate(D:20251218143205)/Producer(Processing-CLI)>> |

| 4 | 18 | 352 | ProcSet resources array | [/PDF/Text/ImageB/ImageC/ImageI] |

| 5 | 22 | 384 | Resources dictionary for the page | <</Font<</OPBaseFont0 19 0 R/OPBaseFont1 20 0 R>>/ProcSet 18 0 R/XObject<</Im0 8 0 R>>>> |

| 6 | 23 | 472 | Array of 2 indirect references (to content streams) | [21 0 R 4 0 R] |

| 7 | 3 | 486 | Updated Page object | <</Contents 23 0 R/MediaBox[0 0 864 576.75]/Parent 2 0 R/Resources 22 0 R/Thumb 11 0 R/Type/Page>> |

What is very interesting here – from a PDF forensics perspective – is the fact of a hidden document information dictionary that is not referenced from the last (final) incremental update trailer (i.e., there is no Info entry in object 31, lines 3050-3063 below). As such, this orphaned dictionary is invisible to PDF software! This oddity occurs in all other PDFs we’d randomly selected for investigation.

Formatted nicely as an uncompressed object, this hidden document information dictionary inside the compressed object stream contains the following information (the CreationDate and ModDate appear to change in other randomly examined PDFs):

17 0 obj

<<

/CreationDate (D:20251218143205)

/ModDate (D:20251218143205)

/Creator (OmniPage CSDK 21.1)

/Producer (Processing-CLI)

>>

endobj

This metadata clearly indicates the software DoJ used to manipulate these PDF files. Although not relevant to the content, this forensic discovery clearly shows that extra care is required when sanitizing PDFs.

Different incremental updates

Another randomly selected PDF, VOL00003\IMAGES\0001\EFTA00003939.pdf contains 3 full-page images, and just a single incremental update that applies the Bates numbering. However, in this case the file header is %PDF-1.5 yet both the original PDF and incremental update use conventional cross-reference tables! This isn’t problematic, but is certainly unexpected and inefficient since PDF 1.5 introduced compressed cross-reference streams.

By comparing the objects in the incremental cross-reference table to the original cross-reference table we can see that objects 66 to 69 – the 3 Page objects for the 3 page document – were redefined. This is just what is expected in order to add the Bates number to each page’s Contents stream as in the previous example.

Metadata

Our initial examination using pdfinfo utilities did not identify any metadata in any of the PDFs in the tranche, either in the document information dictionary (PDF file trailer Info entry) or as an XMP metadata stream (Metadata entry).

However, since we know that (a) the tranche includes PDFs with incremental updates, and (b) that an orphaned document information dictionary exists, all revisions of a document should be thoroughly examined. Incremental updates may have marked other document information dictionaries or XMP metadata streams as free but not deleted the actual data.

XMP metadata is always encoded in PDF as a stream object, and since stream objects cannot be in compressed object streams, using forensic tools to search for keys “/XML” or “/Metadata” should always locate them. All modern office suites and PDF creation applications will generate XMP metadata when exporting to PDF. As XMP is usually uncompressed, searching for XML fragments may also be helpful (see below for an example XMP object fragment).

3 0 obj

<</Length 36996/Subtype/XML/Type/Metadata>>

stream

<?xpacket begin="" id="W5M0MpCe … zNTczkc9d"?>

<x:xmpmeta xmlns:x="adobe:ns:meta/" x:xmptk=" … ">

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#">

<rdf:Description rdf:about=""

xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/"

xmlns:xmp="http://ns.adobe.com/xap/1.0/"

...

Not unsurprisingly for properly-redacted files, we did not find any XMP metadata streams or XML in any PDF. As a consequence, none of the PDFs can declare conformance to either PDF/A (ISO 19005 for long-term archiving) or PDF/UA (ISO 14289 for accessibility). Of course, as untagged PDFs, the files cannot conform to accessibility specifications such as PDF/UA or WCAG in any event. Additionally, none of the PDFs appear to include device-independent color spaces.

The presence of an Info entry in the trailer dictionary or (in PDFs with cross-reference streams) in the cross-reference stream dictionary indicates the presence of document information dictionaries. “/Info” does indeed occur in many of the PDFs, including multiple times in some PDFs, indicating potential changes via incremental updates. However, as discovered above, in some cases the final incremental update does not include an Info entry, thus “orphaning” any existing document information dictionaries.

ISO 32000-2:2020, Table 349 lists the defined entries in PDF’s document information dictionary (Title, Author, Subject, etc). Any vendor may add additional entries (such as Apple does with its /AAPL:Keywords entry), so redaction and sanitization software should be aware of extra entries.

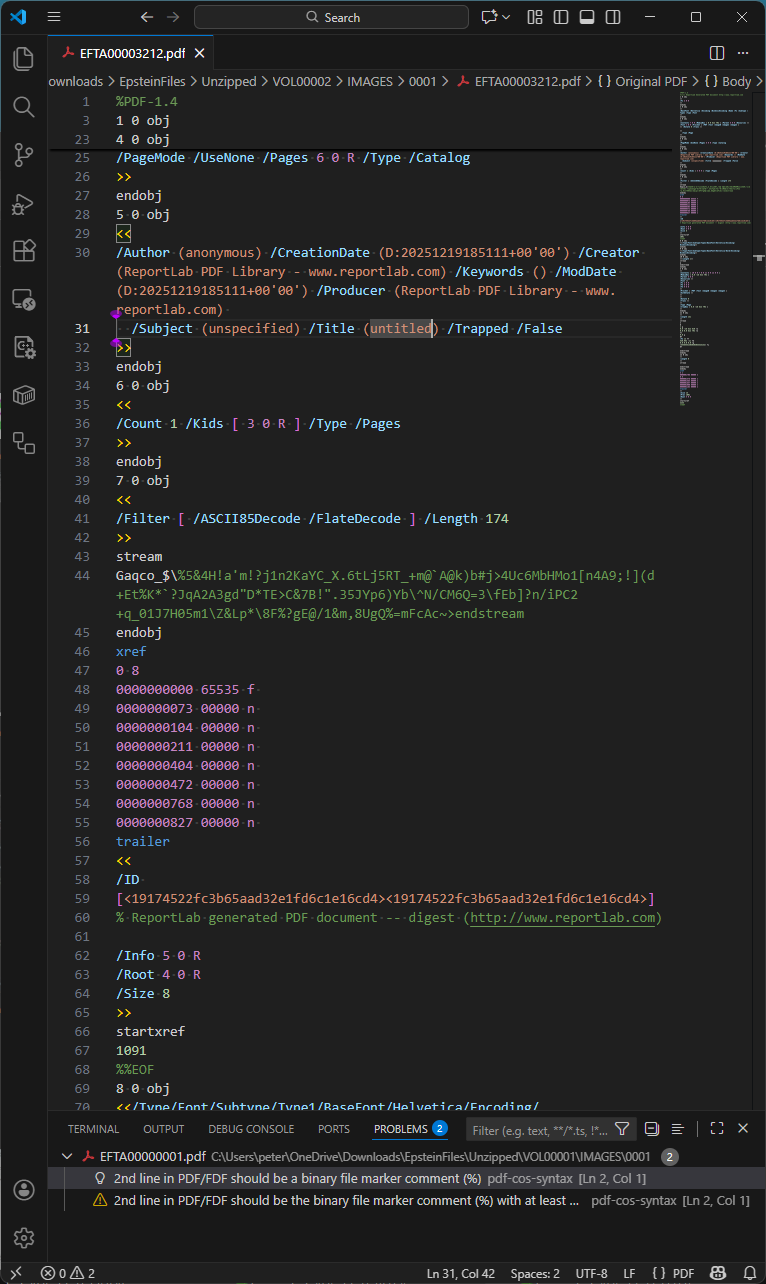

From our random sampling, we identified one PDF with a non-trivial document information dictionary still present: VOL00002\IMAGES\0001\EFTA00003212.pdf. This is shown below in Visual Studio Code with my pdf-cos-syntax extension:

Of additional interest in this specific PDF is that the comment at line 60 has survived DoJ’s sanitization and redaction workflow! Other PDF comments may therefore also be present in other files.

EFTA00003212.pdf appears to be a redacted image or an error from the DoJ workflow, as it is a single page with the text “No Images Produced”.

Simple searching of the standardized PDF document information dictionary entries gives the following (note that the technique used will not locate information in compressed object streams, as mentioned above):

| Key name | Number of PDFs (max. = 4,085) | Comment |

| Info | 3,823 | Some PDFs have empty Info dictionaries with no entries |

| Title | 1 | Only EFTA00003212.pdf |

| Author | 1 | Only EFTA00003212.pdf |

| Subject | 1 | Only EFTA00003212.pdf |

| Keywords | 1 | Only EFTA00003212.pdf |

| Creator | 1 | Only EFTA00003212.pdf |

| Producer | 215 | Always “pypdf” (denotes https://pypi.org/project/pypdf/) |

| CreationDate | 3,609 | Same PDFs that have ModDate with an identical value |

| ModDate | 3,609 | Same PDFs that have CreationDate with an identical value |

| Trapped | 1 | Only EFTA00003212.pdf |

| APPL:Keywords | 0 |

Date analysis

Detailed date analysis is a common task in the forensic analysis of potentially fraudulent or modified documents. However, in the case of redacted or sanitized documents, where the document is known to have been modified, this can be less useful.

The creation and modification dates for the 3,609 PDFs range from December 18, 2025, 14:32:05 (2:32 pm) to December 19, 2025, 23:26:13 (almost midnight). For all files, the creation and modification dates are always the same. This may also imply that the DoJ batch processing to prepare this tranche of PDFs took at least 36 hours!

What’s also interesting is that the CreationDate and ModDate fields in the hidden document information dictionary (inside the object stream of the first increment update – see above) appear to always be an exact match to both the CreationDate and ModDate of the original document. This implies that all dates across all incremental updates were updated in a single processing pass that applied the Bates numbering.

Photographs

There are no JPEG images (DCTDecode filter) in any PDF in the tranche, including the full-page photographs. Randomly viewing the photographic images at high magnification (zoom) in PDF viewers clearly shows JPEG “jaggy” compression artifacts. All photographic images appear to have been downscaled to 96 DPI (769 x 1152 or 1152 x 769 pixels), making text on random objects in the photos much harder to discern (see the OCR discussion below).

DoJ explicitly avoids JPEG images in the PDFs probably because they appreciate that JPEGs often contain identifiable information, such as EXIF, IPTC, or XMP metadata, as well as COM (comment) tags in the JPEG bitstream. This information may disclose the camera model and serial number, GPS location, camera operator details, date/time of the photo, etc., and is more difficult to redact while retaining the JPEG data. The DoJ processing pipeline has therefore explicitly converted all lossy JPEG images to low DPI, FLATE-encoded bitmaps in the PDFs using an indexed device-dependent color space with a palette of 256 unique colors (which reduces the color fidelity compared to the original high-quality digital color photograph).

Scanned documents – or are they?

Randomly inspecting the tranche discovers many documents that appear to have been created by a scanning process. On closer inspection, there are documents that have tell-tale artifacts from a physical scanning process, such as visible physical paper edges, punched holes, staple marks, spiral binding, stamps, paper scuff marks, color blotches and inconsistencies, handwritten notes or marginalia, varying paper skew, and platen marks from the physical paper scanning processes. For example, VOL00007\IMAGES\0001\EFTA00009440.pdf shows many of these aspects

There are also other documents that appear to simulate a scanned document but completely lack the “real-world noise” expected with physical paper-based workflows. The much crisper images appear almost perfect without random artifacts or background noise, and with the exact same amount of image skew across multiple pages. Thanks to the borders around each page of text, page skew can easily be measured, such as with VOL00007\IMAGES\0001\EFTA00009229.pdf. It is highly likely these PDFs were created by rendering original content (from a digital document) to an image (e.g., via print to image or save to image functionality) and then applying image processing such as skew, downscaling, and color reduction.

The use of the timeless monospaced (also known as fixed-width) “Courier” typeface means that the number of characters redacted can be easily determined by vertical alignment with text lines above and below each redaction. In some instances, this may reduce the possible number of options that represent the redacted content, allowing it to be more easily guessed. Although redaction of variable-width typefaces is far more complex, Bland, M., Iyer, A., and Levchenko, K. 2022 paper “Story Beyond the Eye: Glyph Positions Break PDF Text Redaction” showed that this is still possible with sufficient computing power and determination.

Optical Character Recognition (OCR)

OCR is complex image processing that attempts to identify text in bitmap images. In PDF files, OCR-identified text is commonly placed on top of the image using the invisible text render mode. This enables users to then extract the text from the image.

Returning to the very first PDF file in the tranche, VOL00001\IMAGES\0001\EFTA00000001.pdf - this is a full-page photo of a hand-written sign where part of the hand-written information is explicitly redacted. The PDF contains largely inaccurate OCR-ed text, indicating that natural language processing (NLP), machine learning (ML), or even language aware dictionary-based algorithms were not used. This means that there will be more errors in the extracted text than is necessary.

With cloud platforms readily accessible and supporting advanced OCR at low cost, anyone is capable of re-processing the entire tranche of PDFs and comparing the OCR results to those provided by DoJ. Even though the page images are low-resolution (96 DPI), rerunning OCR may bring to light additional or corrected information hidden by the original OCR that failed to recognize everything correctly.

The “black box” redactions we investigated were all correctly applied directly into the image pixel data. They are not separate PDF rectangle objects simply floating above sensitive information that was still present in the image and easily discoverable. Yes, sometimes it is that easy…!

Conclusion

We did not set out to comprehensively analyze every corner of every PDF file in the Epstein PDFs, but to present a basic walk-through of some of the challenges and tricks used to conduct a PDF forensic assessment. Our results above were from a small random sample of documents - there may well be outlier PDFs in the data sets that we did not encounter.

The DoJ has clearly created internal processes, systems, and workflows that can sanitize and redact information prior to publishing as PDF. This includes converting JPEG images to low-resolution pixel-only bitmaps, largely removing metadata, and rendering page images to bitmaps. OCR appears to have been widely applied, but is of variable quality.

Their PDF technology could be improved to vastly reduce file size by removing unnecessary objects (e.g., empty content streams, ProcSets, empty thumbnail references, etc.), simplifying and reducing content streams, applying all incremental updates (i.e., removing all incremental update sections), and always using compressed object streams and compressed cross-reference streams. Information leakage may also be occurring via PDF comments or orphaned objects inside compressed object streams, as I discovered above.

PDF forensics is a highly complex field, where variations in files and tool assumptions can easily yield false results. The PDF Association hosts a PDF Forensic Liaison Working Group to develop industry guidance on forensic examination of PDF files and to educate document examiners and other specialists about many of these aspects.