DoJ reposts the Mueller Report

As CEO, Duff coordinates industry activities and promotes the advancement and adoption of PDF technology worldwide.

As reported within hours by Quartz, four days after its initial release and fanfare-free, the US Department of Justice re-posted the Mueller Report PDF with a few improvements.

They also added a few problems that really shouldn't be present in such a significant historical document.

The Mueller Report

A Technical and Cultural Assessment of the Mueller Report PDF

Even with OCR, the Mueller Report PDF isn't fully searchable

DoJ reposts the Mueller Report! (this article)

The Mueller Report

A Technical and Cultural Assessment of the Mueller Report PDF

Even with OCR, the Mueller Report PDF isn't fully searchable

DoJ reposts the Mueller Report! (this article)

We're written about the Mueller Report PDF twice before; the first time to draw attention to the poor quality of the document's presentation, the second time to highlight clearly for researchers, attorneys, and journalists the perils of relying on OCR to search redacted documents. Our analysis was followed by others; I want to call out in particular an article by Martin Nikel, whose analysis goes far deeper into the text than our own.

In this piece we analyze the Justice Department's 2nd attempt at posting a Mueller Report worthy of history. We explain the improvements DoJ made and identify remaining (and newly introduced) weaknesses.

We do this not to embarrass DoJ or the Office of the Special Counsel, but to call attention to the significance of how documents are created handled and processed in the hope that such situations can be avoided in the future.

OCR for searchable text

DoJ used Adobe Acrobat DC software to OCR the document, adding approximately 5 MB of searchable text and structure tags to the file. The same software (one assumes) also provided better image compression for a final size of 137 MB, 2 MB smaller than before, but still 10-20 times larger than a born digital PDF.

Critique

The OCR results, while adding a degree of searchability, nonetheless includes the same gaps and scrambles in the searchable text as we'd previously documented. Although the new report is more searchable than the entirely textless file DoJ first posted, it's far from reliable, with at least a thousand words simply not OCRed at all, and thousands more scrambled.

This could have been forgiven in... 1999. But the year is 2019. 26 years after the introduction of PDF, over 20 years since PDF became the de facto electronic document format. No-one imagines that Mueller bashed out his report on an IBM Selectric so it remains fair to ask: why didn't DoJ simply redact and release Mueller's PDF? Did they even receive a PDF from Mueller? Or did Mueller choose not to deliver a PDF to DoJ, but only deliver his report on paper? And if so… why?

Tags for accessibility

Tags are a feature of PDF introduced in 2000 for the explicit purpose of making it possible for assistive technology (screen readers, zoom viewers, braille printers, etc.) to present the contents of a PDF document to users with disabilities. They have other useful capabilities as well. Tags make it easier to repurpose PDF content in many settings, from copy/paste to reflowing text. More significantly for the Mueller report, the Section 508 regulations require federal agencies to post accessible content, including tagged PDF files, as DoJ knows well.

By opting for a workflow in which they printed, scanned and OCRed a redacted document DoJ created a situation where they forced themselves to deal with lots of trashed (missing or scrambled) text, images confused as text, text confused as images and more.

Regardless, DoJ made a real (if ultimately unsuccessful) effort to make the report accessible.

Positive changes

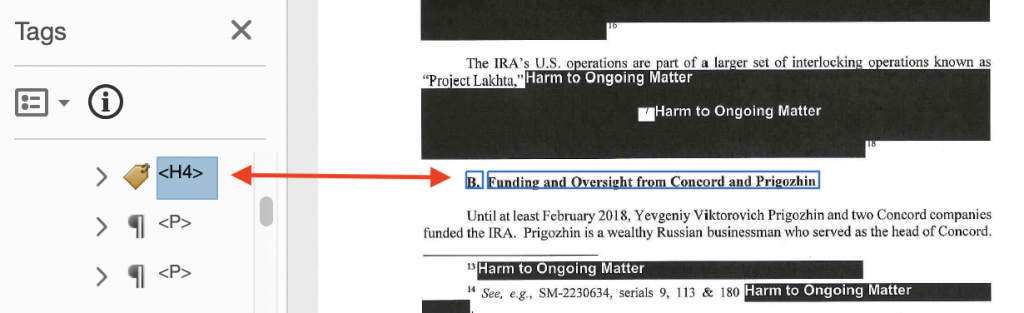

- DoJ added tags, probably during the OCR process.

- For each of the Figure structure elements they attempted to add alternate text.

- In some cases where the redact-print-scan workflow had blatantly trashed OCR results they even attempted (this would have been laborious!) to "clean up" the bad OCR results by sticking the missing text into the alternate text properties of a nearby redaction's Figure structure element.

Critique

We have a great deal of sympathy for DoJs accessibility remediation staff. Clearly, the bosses told them to "fix it fast!" and they tried. Sadly, due to the fact that they were working with a scanned printout of a redacted document, the result cannot be called accessible for the following reasons:

- The OCR errors are uncorrected; the affected text remains both unreliable for search purposes and (often) unreadable by assistive technology.

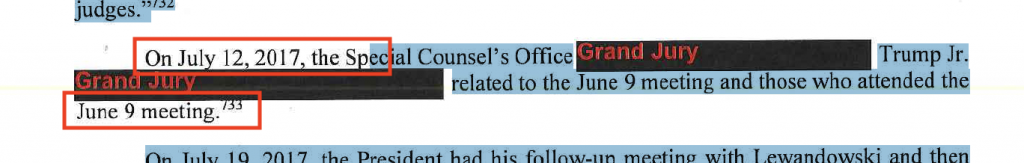

- As mentioned above, aware that the redaction marks were creating egregious OCR errors, DoJ attempted to account for this problem by "restoring" missing text by including it in the alternate text for a nearby redaction. A good example is found at the top of page 44 (PDF page 52). This approach is invalid because it leaves downstream users and software with a confusing impression about what's an image, what's redacted and what's text. It also renders search results inconsistent, since not all search software supports tagged PDF.

- The automatically-generated tags were inadequately quality-controlled. We see this in many ways including (but not limited to):

- Page headers and page-numbers are tagged when they should be untagged artifacts (throughout)

- Many redactions are untagged (e.g., page 29, PDF page 37), others are tagged as text (e.g., page 31, PDF page 39) while others are tagged as Figures with alternate text giving the redaction's purpose.

- Some images are tagged as paragraphs (e.g., page 31, PDF page 39)

- Some tags are in incorrect logical reading order (e.g., page 31, PDF page 39)

- Footnotes are tagged inline with the page, breaking the reading order between pages (throughout)

- Many headings are tagged as paragraphs (throughout)

- Many paragraphs are incorrectly tagged with multiple paragraph tags. (throughout)

For the above reasons (as well as some others, but this piece is already too long), the 2nd version of the Mueller report cannot be said to be accessible or conform with Section 508. Users with assistive technology will find this file unreliable and inefficient, and will not be able to use the system of headings provided by the document's authors.

All the these problems were driven by the workflow. If Mueller had delivered a tagged PDF it could have been redacted and delivered without the horror of printing and scanning a perfectly functional, searchable, accessible and securely redacted PDF file!

Shouldn't government records be properly usable without all this chutney? It's past time for a law!

If you wanted another reason to fix the workflow...

It's not strictly speaking an accessibility issue, but I would also call to DoJ's attention the fact that for in more than a few redactions (e.g., on page 34, PDF page 42) incorrect alternate text was added so that, for example, a redaction marked in the document as "Personal privacy" now includes alternate text indicating a different purpose (e.g., "Harm to ongoing matter").

As with the accessibility issues, this type of problem isn't so much a human error as the all-too predicable outcome of a workflow that's trying to clean up the original mess created when DoJ decided on a redact-print-scan workflow.

Keep that document digital, please!

Bookmarks

The old report did include bookmarks, but they were arbitrary, unintended and added no navigational value. In the new report.pdf, DoJ has provided new bookmarks for each of the document's top-level headings.

Critique

Bookmarks are an immense help to navigation for all users, as they provide an interactive table of contents alongside the document. In longer documents such as the Mueller report it is far preferable to have the bookmarks at least match (if not extend) the document's own table of contents.

When adding bookmarks it's preferable to set the file to show the bookmarks automatically when the document is opened. If not, most users never find them.

Links

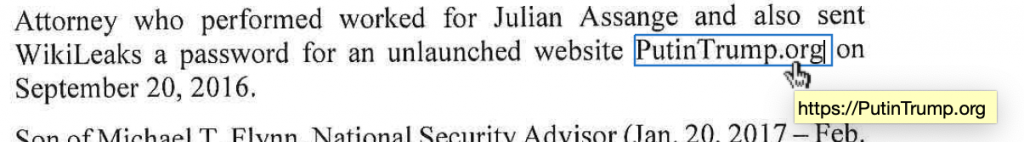

The software DoJ used for OCR looks for URLs and email addresses and automatically adds links to the document when it finds them.

Critique

Automatically adding links can lead to an unfortunate situation where the Mueller report itself links to dubious websites and email addresses (such as that of Russia's Internet Research Agency or Guccifer20). These links were almost certainly not intended by Mueller or DoJ; they were probably unaware that the software would add these links.

Given the placement of the file (on DoJ's servers) and its significance, these links have the potential to send users reading the report to unsafe websites, scramble or corrupt search engine optimization and/or website reputation and other misdemeanors. DoJ's policy should be to scrub out-links from documents it posts on its site unless such links are intended.

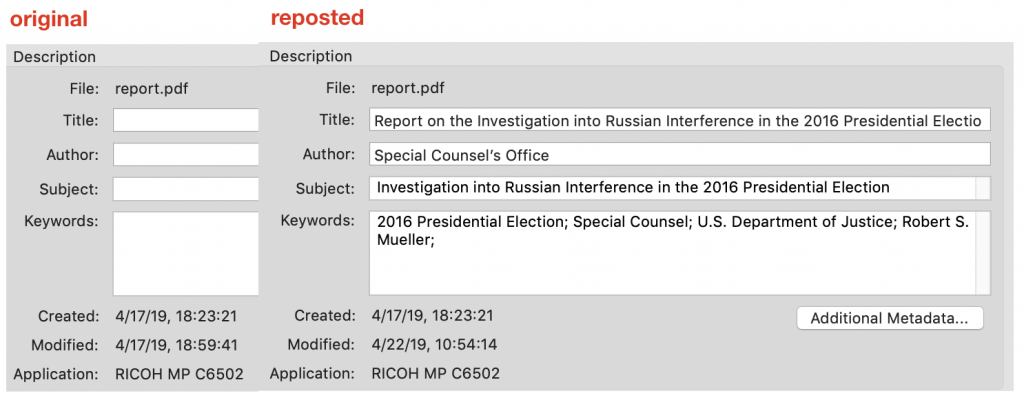

Metadata

The first edition of the Mueller report was woefully lacking in a way we didn't even cover before: metadata. The revised file now includes proper metadata to improve the document's searchability and performance in search results and to facilitate organization in content management systems.

Best practice

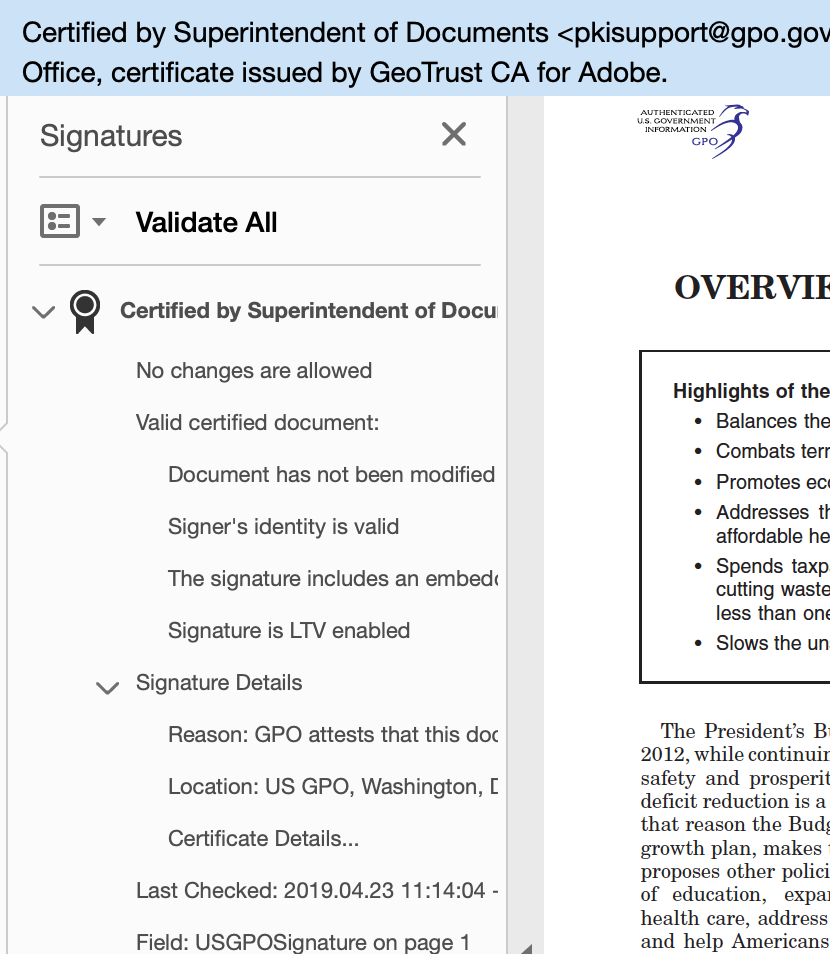

PDF technology includes a variety features that are highly relevant to historical and other vital government and business documents. These features are well-known to the government.

For example, the Government Printing Office (GPO) routinely uses digital signatures to assure readers that its publications are authentic and have not altered. The formal guidance provided by the National Archives identifies PDF/A as a preferred format. Why doesn't DoJ follow these best practices? The concept of a chain-of-custody is perhaps more familiar to law enforcement organizations as it is to anyone, and mature digital signature technology has been available as a feature of PDF for over a decade.

Conclusion

Back in the days of paper documents these workflows didn't have IT implications, budgetary or otherwise. Now they do, and if the government is going to hit its target for going all-digital for its records by 2023 it's got a lot of work to do.

Congressional action

At the end of the day we believe that Congressional action is necessary to give the Government Printing Office and the National Archives and Records Administration some teeth so they can begin to compel other agencies to use modern best practices in the handling of valuable and especially archival documents, PDF files, source documents, email and beyond.

PDF technology is a pervasive feature of the world's communications infrastructure. With a unique and unmatched feature-set; no other technology comes close. We're not going back to paper, so it's long past time for governments and businesses to focus just a little on this ubiquitous format that's never going away.