Even with OCR, the Mueller Report PDF isn’t fully searchable

As CEO, Duff coordinates industry activities and promotes the advancement and adoption of PDF technology worldwide.

On April 19 we published an analysis of the Mueller report PDF released by the US Department of Justice. Further analysis of the PDF file reveals an additional serious problem.

Even after running OCR software, the report isn't truly searchable.

Take-aways

- The workflow DoJ chose for releasing the PDF of Mueller's report makes the work of OCR software vastly more difficult. A non-trivial volume of the Mueller Report is not searchable by users who must rely on OCR results. DoJ could have avoided this result.

- Courts and attorneys need to consider the interaction between redaction, scanning and searching in their document management practices.

The Mueller Report

A Technical and Cultural Assessment of the Mueller Report PDF

Even with OCR, the Mueller Report PDF isn't fully searchable (this article)

The Mueller Report

A Technical and Cultural Assessment of the Mueller Report PDF

Even with OCR, the Mueller Report PDF isn't fully searchable (this article)

Background

When starting from an images-only PDF, making the file text-searchable requires the use of optical character recognition (OCR) software. Unfortunately, OCR software is limited in its ability to distinguish text from non-textual content (such as redaction marks). Put simply, text in close proximity to non-textual content can confuse the software, resulting in unsearchable text.

Unsearchable content in the Mueller Report

Unfortunately for the President's lawyers, Congress, other lawyers, researchers, journalists, preservationists and the interested public, they cannot rely on the results they get from OCR, as we show below. There is a solution, which we explain, but it's hardly an acceptable alternative.

Below are a few screenshots produced after processing the original report with the OCR provided in Adobe Acrobat DC. Other software will produce somewhat different results, but few (none) will accurately capture all the text.

Searches for names, dates, places, references, evidence… they all depend on text search. The DoJ’s choice in how they delivered this document has made accurate text search impossible for all downstream users of the document.

In these screenshots the blue highlights show what text was captured (at least in principle) by my OCR software. The un-highlighted text was entirely missed, and is therefore not searchable.

The examples below are just from the first few pages, and are by no means the most egregious examples. The problem is pervasive.

In the caption below each screenshot we provide the text extracted by OCR. As is easy to see, the text quality degrades very significantly when the text is close to a redacted area.

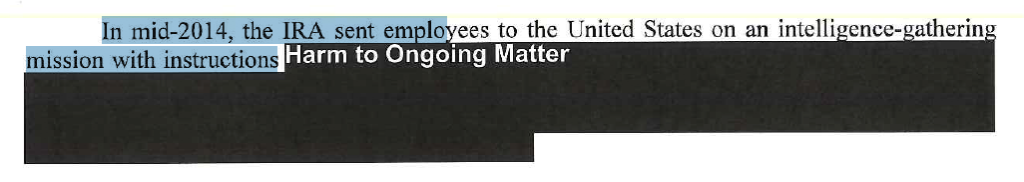

Page 4 (12th page of the PDF)

mission with instructions

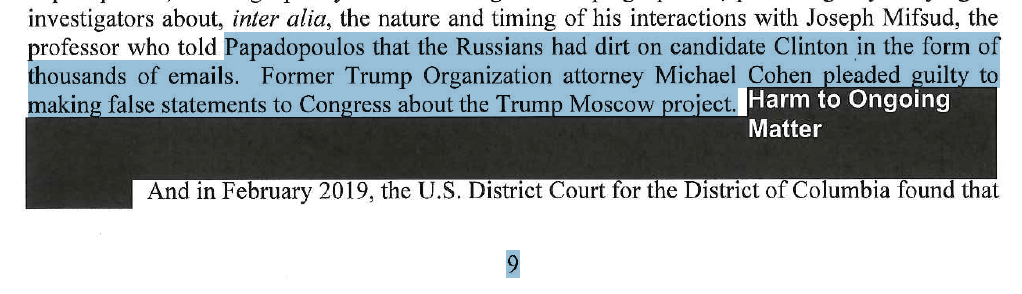

Page 5 (13th page of the PDF)

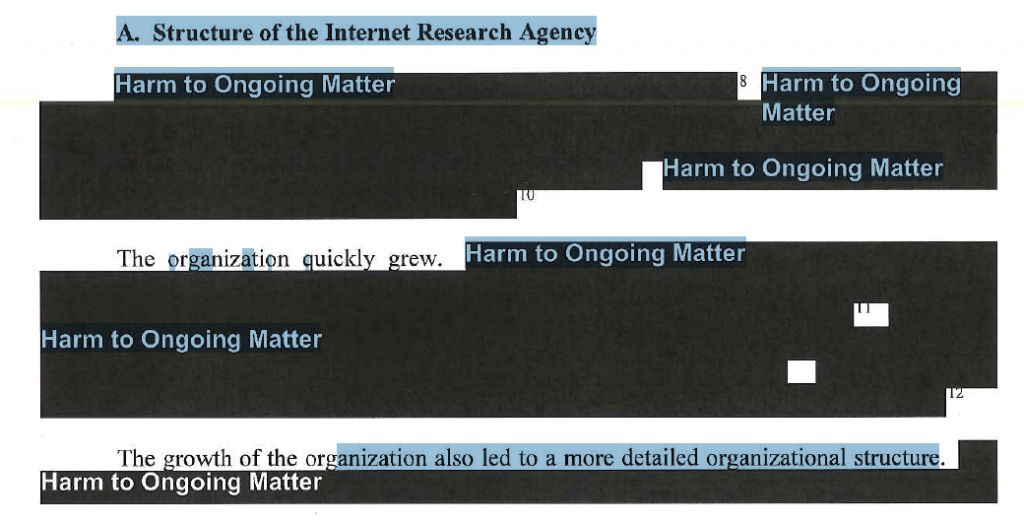

Page 15 (23rd page of the PDF)

Harm to Ongoing Matter Harm to Ongoing

Matter

Harm to Ongoing Matter

I ! " " I I Harm to Ongoing Matter

Harm to Ongoing Matter

anization also led to a more detailed or anizational structure.

Redaction software

Professional-grade PDF redaction software has been available for over two decades, and is proven trustworthy. Dedicated software isn't necessary; many better PDF editors include redaction features alongside other PDF editing tools. The problem here isn't the tools; it's the workflow.

A solution (of sorts)

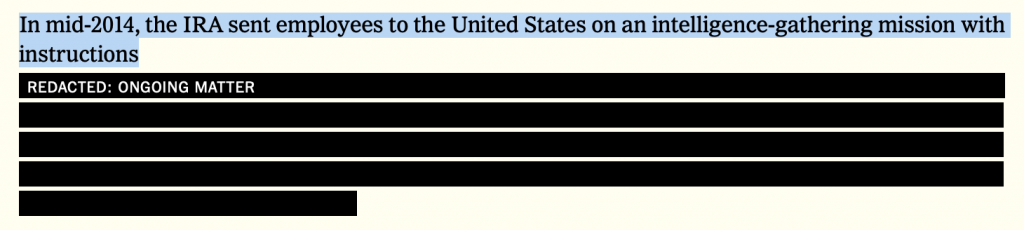

Given what was released, there's only one way to search the PDF with any assurance; a complete reconstruction of each page. This is exactly what the New York Times has done. The screen-shot below shows the Times' fully-searchable reconstruction of the first screen shot I provided above.

The method the Times used to present a genuinely fully-searchable version of the Mueller report is elaborate, and required the services of 22 people (they are credited at the bottom of the page); even so, they were not able to fully mimic the original pages. The result is functional but extremely expensive, both in staff time and computing resources (my browser complains that the Times' page is "using significant memory"). Of course, it's also not the authentic page.

Conclusion

This unfortunate reality could have been avoided if DoJ's workflow was simply redact-release instead of redact-print-scan-release (or even worse: print-scan-OCR-redact-print-scan-release). They chose a method that did not improve the security of redacted content but did materially and negatively burden everyone who would try to read, consume or otherwise process this document, forever.

We know that DoJ knows better, as we've previously observed that they use professional redaction software. In our view it's simply unacceptable that they should choose an unnecessary belt-and-braces approach for this historically-significant document that impedes every downstream user.

Implications for attorneys, journalists and others who are professionally reliant on OCR

The fact is: redacted documents OCR poorly. Lawyers redact documents all the time, and they rely on OCR to make scanned documents searchable. Perhaps, given the propensity for invalid search results in redacted-then-scanned documents, courts will begin to require production of born digital PDF documents when available, and not accept scans as a substitute.

PDF is a wonderful technology for documents, and it's great for accommodating scanned pages, but PDF can do so much more. Learn more about it at the Electronic Document Conference this June in Seattle! There's even a session specifically about best practice in PDF redaction!